The Women, Work, and the Gig Economy consortium joins a growing research stream that seeks to make sense of women’s work in a labour market experiencing rapid technological transformations. In this, the ‘Ecosystems of Engagement’ project – involving the Centre for Policy Research, LIRNEasia, the Indian Institute of Human Settlements and the World Resources Institute – takes a multi-stakeholder multi-sectoral approach. The project collects insights from platform companies and women partners and brings these into conversation with policy experts, academicians and practitioners in the areas of labour, employment, gender and digital governance.

Given the ambitious scope of the work, we started by looking for a way to tie together disparate ideas, literature and perceptions into a coherent framework. Given the project’s focus on gender, in June 2020 we started exploring the idea of building our research around Naila Kabeer’s Gender Empowerment Framework, which has already been widely used to examine the links between paid work and ‘empowerment’, which can be a nebulous and loosely used term in development research and practice. Given that much of the literature on women’s work in India pointed to constraints to women’s agency posed by social norms, the framework’s integration of contextual factors like social norms and institutions seemed particularly relevant to our ‘ecosystems’ approach. But how could we be sure that a theoretical framework will fit the empirical data that we were yet to collect?

In cracking this dilemma, we piggybacked on existing research material from project partner LIRNEasia’s older qualitative research work with online freelancers in India, which involved 52 focus group discussions and 18 interviews with men and women aged 16-40 engaged in online freelance work in urban centres in India, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar. This data was not collected or analysed with Kabeer’s framework in mind and focused on identifying the nature of online freelancing and the barriers and constraints to this type of work.

We analyzed a total of 13 transcripts – 6 in-depth interviews (IDIs) and 4 focus group discussions (FGDs) from India and 1 IDI and 2 FGDs from Sri Lanka – using the proposed framework to check if it helped us make sense of the data and answer our key research question on whether paid work on digital platforms is empowering for women. Some of these transcripts involved conversations with men and mixed-gender groups as well. This blog explains how we did this, what we learnt and how this was incorporated into our research methodology.

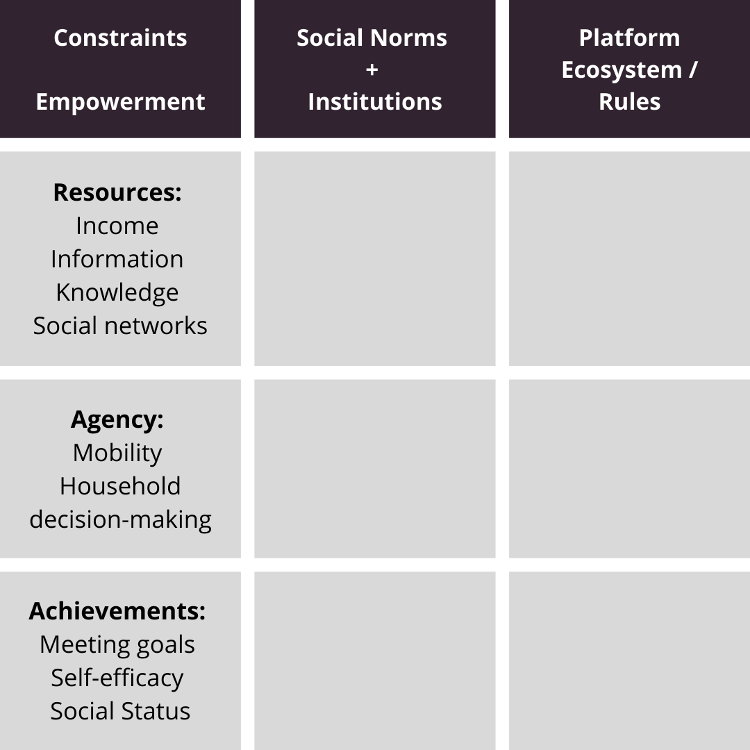

The adapted framework under ‘testing’

Kabeer views gender empowerment as a change in power relations, such that women’s experiences and outcomes change along the following three broad parameters:

(a) Resources: gaining access to material, human, and social resources that enhance people’s ability to exercise choice, including knowledge, attitudes, and preferences;

(b) Agency: increasing participation, voice, negotiation, and influence in decision-making about strategic life choices;

(c) Achievements: the meaningful improvements in well-being and life outcomes that result from an increasing agency, including health, education, earning opportunities, rights, and political participation, among others.

Kabeer’s framework avoids absolute measures or universal indicators and proposes two additional context-specific variables. These “structures of constraint” shape the process and extent of empowerment afforded to women, viz.:

(d) Norms: unwritten but socially-enforced rules, gender roles, expectations, and standards of behaviour; and

(e) Institutions: norms + formal structures, rules, procedures

Figure 1: Template for transcript analysis based on Kabeer’s framework

A transcript analysis workshop

We conducted a workshop involving all partner institutions to analyze the existing transcripts from LIRNEasia’s project, in order to learn how resources, agency and achievements impacted or were impacted by online freelance work, especially for women. We also examined transcripts for material on structures of constraint, since platforms ecosystems interact with and are influenced by existing norms and institutions, but are themselves composed of infrastructure networks, rules, policies and protocols which might constrain/ support or enable/ facilitate women’s empowerment.

To do this, we first developed a matrix based on the Gender Empowerment Framework (see Fig 1). We selected 11 protocols with female respondents (2 had mixed-gender respondents). Later we added two protocols with male respondents to offer a comparative perspective. We had ten workshop participants who analyzed 1-2 transcripts each using the matrix. We discussed insights from each transcript during the workshop.

Questions that emerged

Without getting into findings per se, we highlight those aspects that emerged from our analysis, which subsequently fed into the questionnaire we used for the semi-structured interviews conducted under the ‘Ecosystems of Engagement’ project.

Resources and agency are contingent on identity, social norms

The transcript analysis revealed that social networks are important resources in accessing platform work. Endorsements through peer and family networks are valuable to legitimize women’s work and influences the selection of work platforms. We were alerted to the advantages that might come with better social status (in terms of caste and class, for instance) and better location.

Income levels appear to impact the agency of women in interacting with platforms, for instance in their ability to take or leave work, demand payments or fairer timelines, etc. Similarly, higher skill levels allow women to take more risks on platforms. Despite these differences in women’s levels of resources, social norms within households could impact mobility, access to public space and the ability of women workers to connect with peers.

Women’s responses need deeper probing

Women freelancers valued the flexibility offered by tech platforms. In terms of achievements, this allowed women to balance remunerative work with unpaid care work, though the importance of an income, whether substantive or only adequate for personal expenditures, was a recurring theme. This sensitized us to the need to probe respondents around themes of well-being, agency, rights and political participation, beyond their own expectations, which appeared to be constrained by patriarchal norms.

It was also not always clear whether women reflected their own individual goals in their narratives, or do they by default present their achievements keeping their position within the household in mind. This blurred positionality reminded us to be mindful of the scale at which agency is being exerted by women platform workers. Are they representing themselves as individuals, household members, members of another closed group or as women in society at large?

Gendered perceptions of work did not only impact women. While women’s work on platforms is largely positively perceived within households, men are expected to go out and earn a living, with the ‘9-5’ job being the norm. These gendered perceptions likely play into women’s own sense of achievement and self-efficacy as well as the resources that households provide to them for platform work. Inter-generational attitudes towards platform work also differ and therefore the impact on young workers’ resources, agency and achievements could differ from older ones.

How gendered are institutionalised aspects of work?

Overall, women favoured platform work, perceiving it to be fairer to them as compared to physical jobs. Some women felt it was much harder to navigate a hierarchical and competitive human resources structure in offline jobs. We learnt that it is important to pay attention to women’s relationships with institutional structures and procedures. For instance, the analysis revealed that as compared to women, male respondents were very aware of how platform processes and algorithms work, enabling them to negotiate rates and “game” the algorithm. Is this a matter of the effort needed to gain this understanding and work it to your advantage, something that women lose out on because of time poverty? Or is interaction on digital platforms impacted by gendered norms of behaviour, e.g. assertiveness, that mirror features of the physical workspace? Conversely, what can platforms do to address inherent inequalities by redesigning algorithms and user interfaces?

Given the importance of skills, it is pertinent to enquire what kind of entry barriers are created if platform communications and training materials are targeted to people who already have a certain level of knowledge and skills. Are women disadvantaged not on account of their gender, but because platform algorithms are implicitly factoring it in through other variables like skill or time spent on training, where women’s time poverty might disadvantage them?

Taking learnings forward

Not only did the transcript analysis exercise feed into the development of a robust and detailed interview schedule for platforms and workers, but it also gave us the confidence to incorporate the Naila Kabeer Gender Empowerment Framework into the coding of our worker interview transcripts as well. Coding strategies were also ‘workshopped’ with several members of the project team, allowing for cross-learning and an enriched analysis. In the coming months, this collaboration is expected to facilitate comparative analysis between data collected in India and Sri Lanka.

The author would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ayesha Zainudeen, Ramathi Bandaranayake and Tharaka Amarasinghe from LIRNEasia, Shahana Chattaraj, Harshita and Chaitanya from WRI India and Prerna Seth, Aarushi and Tanvi from Centre for Policy Research, who participated in the workshop and contributed to these learnings.