Acceleration of technology and proliferation of labor platforms are creating opportunities for gig work. As this type of work unfolds, what will its impact on workers be, especially women’s agency in negotiating such work? In an effort to understand this better, this brief examines evolving gig work in Thailand’s care economy.

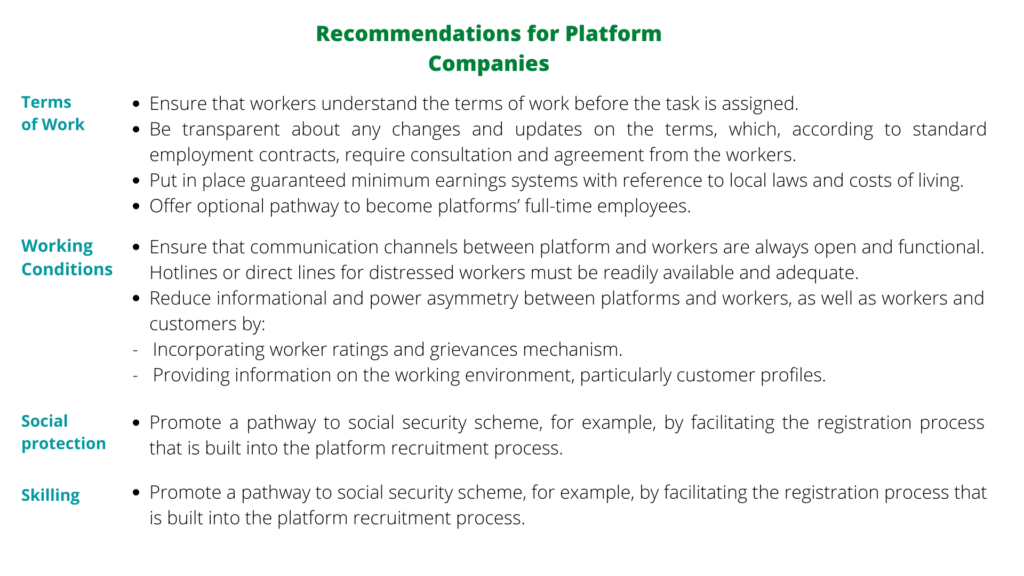

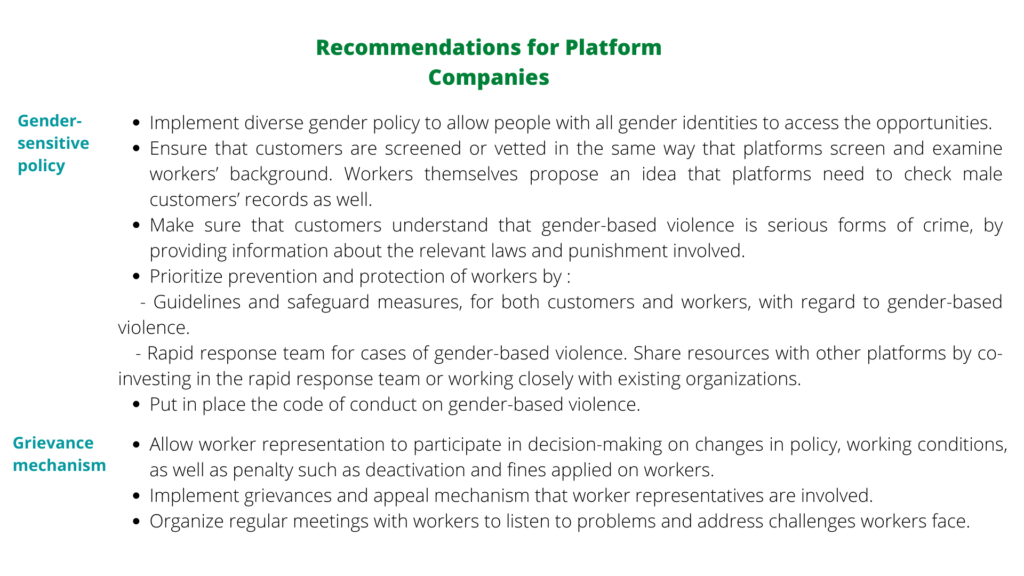

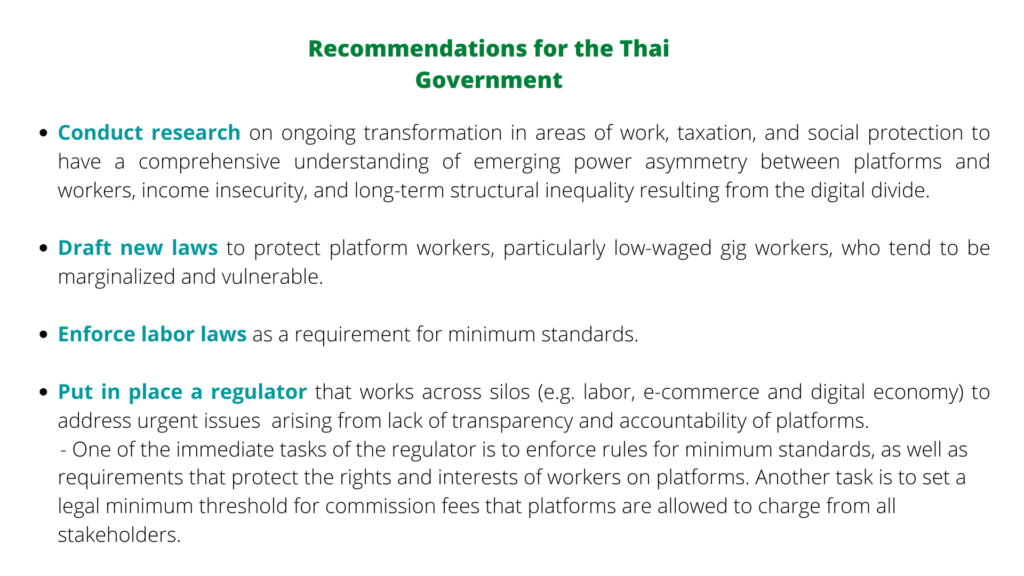

The Thai government has taken a piecemeal approach towards labor platform regulations and the concerns of gig workers. For instance, government agencies have continued to separately draft policy and new laws to address the issues, with limited consultation with relevant stakeholders.

Care labor platforms reproduce gendered divisions of labor by intentionally recruiting women into care work, discriminating against men, gay and transgender individuals. Platform owners and executives still express gender-normative attitudes that women are suitable to perform care work, often considered “feminine.” Care platforms do not only approach womanhood narrowly by focusing on biological sex or sex assigned at birth, but their recruitment and employment practices also reproduce gender biases. Not only do labor platforms reproduce gender norms regarding the traditional role of women in performing care and reproductive work, but they also expose women workers to the risk of gender-based violence.

Despite this, many platforms do not have policies that account for the needs of women workers. This is in part due to common platforms’ design choices. For example, all platforms have a one-sided review system: only customers review the workers but not vice versa. More importantly, as competition increased in the market, platforms became protective of their own reputations, and tended to hide any information that they deemed damaging to their image. This finding is instrumental in changing the understanding of platforms in a way that advances research concerned with gender-responsive technological designs.

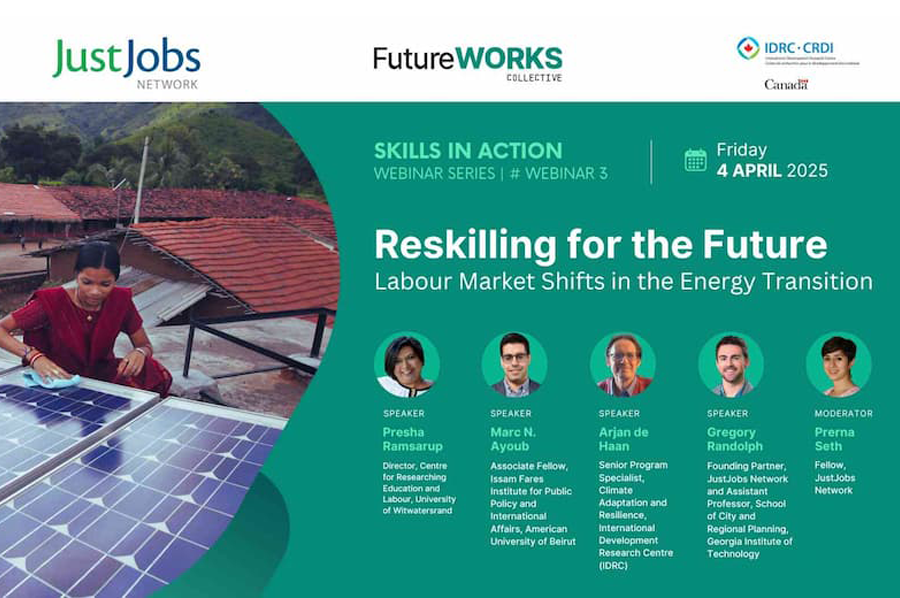

Between January 2019 and June 2021, Just Economy and Labor Institute (JELI), with support from the International Development Research Center Canada (IDRC) conducted action-oriented research on platform-based care workers including domestic workers and massage therapists in Thailand. The study consisted of 295 women workers, among which 148 were domestic workers and 147 were massage therapists in two main locations: Bangkok and Chiang Mai. Two major categories of workers were interviewed among each occupation: traditional gig workers who work offline and platform-based gig workers. This was supplemented by worker focus group interviews, platform executive interviews, and participant observations of new workers training to develop an understanding of the gendered aspects of gig work.

This research centers women’s voices regarding both the positive and negative aspects of platform-based work and aims to strengthen their decision-making power in determining their employment and working conditions. Drawing from a conceptual framework on care work that situates domestic cleaning as “reproductive labor” and masseuses as “nurturant labor” with similarities to “body work”, this report considers both groups as care workers who perform embodied, affective and interactive work. It also raises awareness of the unique impact of the gig economy on flexibility, access, and autonomy of women workers. Finally, the project recommends a set of gender-responsive policies and collaborative empowerment programs for stakeholders.

This research is one of the first to highlight the significance of care work and care workers from a Global South perspective. The literature on labor platforms is largely dominated by case studies from the Global North, which tends to be biased toward more technologically advanced platforms. However, the impact of digitally-mediated labor platforms on predominantly precarious work such as care work in the Global South needs to be acknowledged. This calls for a regulatory ecosystem which centralizes women’s labor issues on platforms, provides social protections to gig workers, and holds platform companies accountable for their gender-blind policies which end up perpetuating discriminatory gender norms and practices.

*This research project is led by research team at Just Economy and Labor Institute in collaboration with two grassroots organization: Empower and MAP foundations. The report is authored by Kriangsak Teerakowitkajorn and Chonthita Kraisrikul.