“Jordan“ (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by ILO PHOTOS NEWS

As we lumber toward the two-year mark of the global pandemic, and continue to count the case numbers and death tolls, this article looks at the impacts that the pandemic has had on household incomes and earning opportunities in India and Sri Lanka. Incomes have been hit hard with many lost jobs, but women bore the brunt. Remote work and platform economy-related earning opportunities provided a cushion during this difficult time,1 but differences in access, awareness, and experiences related to digitally enabled work opportunities point to gender disparities that are not immediately apparent through aggregate statistics.

This reportage delineates the impact of the pandemic on income and earning opportunities of men and women in Sri Lanka and India. This serves as a backdrop for how men and women engaged with the digital ecosystem of work during the pandemic, pointing to how these trends may unfold in years to come.

Incomes took a hit, and have not bounced back

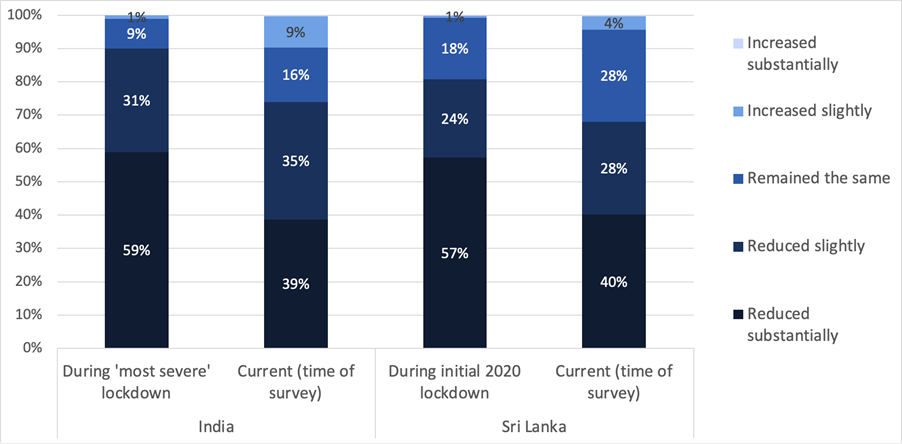

The COVID-19 pandemic had a crippling effect on household incomes; but 2021 survey data shows that even 18 months into the pandemic, many households had still not recovered. For instance, during what respondents considered ‘the most severe’ lockdown (the janta curfew of 2020, for most), 59% in Indian households saw a ‘substantial’ reduction in income (a further 31% reporting a slight reduction) compared to pre-COVID times (Figure 1). Looking closer at the lower socio-economic group households, the picture is much bleaker, for instance with 72% of the lowest category (SEC E) reporting substantial reductions. Female-headed households in India were particularly hard hit, with 65% reporting a substantial drop in household income, compared to 58% of male-headed households. By August 2021, 74% of Indian households still reported that their household incomes were below pre-pandemic levels.

In India, Female-headed households were particularly hard hit, with 65% reporting a substantial drop in household income, compared to 58% of male-headed households. In Sri Lanka, male and female-headed households reported similar changes to their income levels across periods.

Figure 1: Impact of pandemic on household incomes: Comparison of household income to pre-pandemic levels (% of households)

Source: LIRNEasia survey data (2021)

In Sri Lanka, the picture was much the same, with 57% of households having experienced a substantial reduction in their income during the first (and strictest) lockdown, and by October 2021, 68% of households reporting that their incomes were still below pre-pandemic levels. Interestingly, male and female-headed households reported similar changes to their income levels across periods. Once again, the lowest socio-economic category households were hardest hit, with 66% of the SEC E group reporting a substantial reduction in income.

Job loss, men shifting to care work, greater focus on family work

14% of the population aged 15+ in India and 13% in Sri Lanka had lost their job within the initial 2020 lockdowns. These numbers exclude those who were engaged in unpaid family work. While the level of job loss was the same for men and women in India, there was a distinct gender gap in Sri Lanka, with 10% of males compared to 16% of women in the same group having lost their job. The level of job loss during the period reported by respondents that lived in a male-headed household was almost double (15%) that of respondents that lived in a female-headed household (7%) in India. This is at odds with the earlier finding of Indian female-headed household’s incomes being harder hit. The data is not able to shed light on why this is so, but one hypothesis could be that the jobs lost in male-headed households were of higher salary levels than those in female-headed households.

By the time of survey (March-October 2021) 24% of Indians and 40% of Sri Lankans that had lost their jobs were still out of work.

“ILO photo e6322“ (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by ILO PHOTOS NEWS

During the lockdown periods, there were minor shifts of men to unpaid housework, and both men and women to unpaid family work; presumably this is the effect of families putting more effort into family businesses with job losses, and mobility restrictions in place. But by the time of the survey, most respondents had gone back to their pre-pandemic activities.

Remote work not an option for most, harder for women than men

Working from home was observed only in 10% of the Indians, with higher numbers in NCT of Delhi (19%) and Maharashtra (13%). But the data clearly shows the divide between groups, with remote work mostly limited to those in a few sectors (namely, finance, insurance and technology in India), and those with higher levels of education.

In Sri Lanka, 22% of those with a job during lockdown were able to work from home. Again the divides were clear between those who were more versus less educated, and those coming from higher versus lower socioeconomic group households.

“Durga Nandini“ (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by ILO in Asia and the Pacific

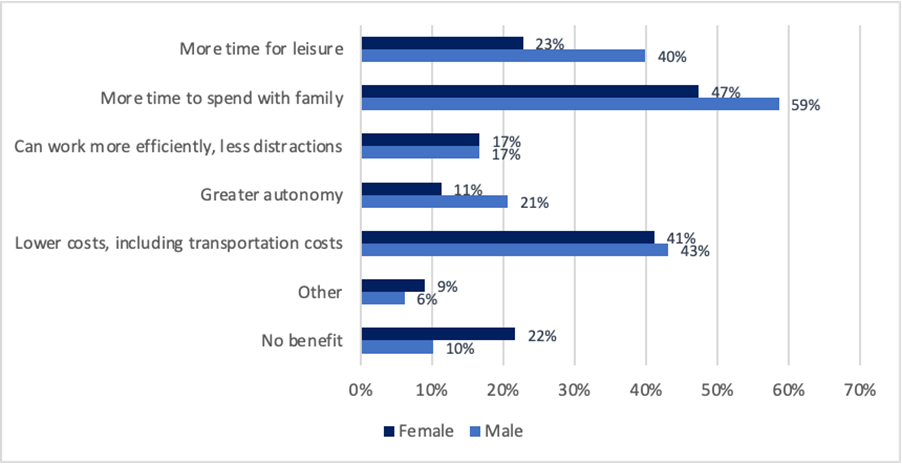

The numbers in India are too small to be disaggregated by gender with any level of statistical confidence. But in Sri Lanka, the gender breaks are telling of the lived experiences of working women during lockdown: When asked about the benefits experienced in remote work, both men and women mentioned the lower transportation costs equally; men were more positive about the extra time that they had to spend with family and for leisure; they also valued the autonomy that they had in their work; a larger proportion of women said they didn’t see any benefit to remote work (Figure 2).

A larger proportion of women said they do not see any benefits of remote work

Figure 2: Perceived benefits experienced in working remotely: Sri Lanka (% of 15+ population that worked remotely)

Source: LIRNEasia survey data (2021)

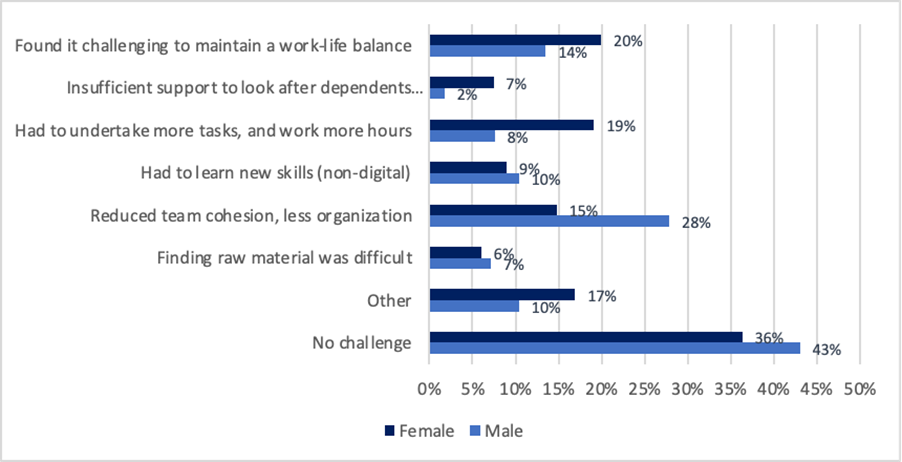

When asked about the challenges in remote work (Figure 3), women faced the most difficulty in maintaining a work-life balance, having to undertake more tasks and work more hours, and not having sufficient support to look after their dependents. Men on the other hand found the reduced team cohesion and less organisation the greatest challenge to remote work.

Women faced the most difficulty in maintaining a work-life balance, while men found reduced team cohesion and less organisation more challenging.

Figure 3: Challenges experienced in working remotely: Sri Lanka (% of 15+ population that worked remotely)

Source: LIRNEasia survey data (2021)

What role did the platform economy play? Limited at best, especially for women

In India, less than a quarter (23%) of the 15+ population was aware of the various possibilities of earning opportunities offered by the platform economy. These range from ride sharing to online freelancing to selling home bakes and crafts over social media or e-commerce platforms. There was greater awareness among men, 29%, compared to women, 16% in India. Sri Lanka had a comparatively higher level of awareness (44%), with women’s awareness more or less on par with men.

The groups that had the highest levels of awareness of this kind of earning opportunity were students, those employed in the public and private sector and the unemployed. Awareness was relatively lower among those, for instance, in unpaid housework, unpaid family workers, the retired, the disabled.

However, when it came to making actual use of these opportunities, just 4% of the 15+ population in India made use of them for earning. Whereas in Sri Lanka, the use was higher at 9% of the same group. In India, there was a visible gender gap in use, with 6% of Indian men compared to 2% of women. The gap in Sri Lanka was not so large. In both countries, those that used platforms the most for earning opportunities were those that were employed in the public or private sector, the unemployed (who were seeking work) and students. Those engaged in unpaid housework (the largest type of work among women in both countries) were the least likely to make use of platform opportunities to earn, in contrast with the common notion that women often turn to the platform economy for the opportunity of flexible work that allows them to take care of house and care responsibilities simultaneously. Just 1% of those engaged in unpaid housework in India and 4% in Sri Lanka were using platforms to earn by mid-2021.

Amidst the job losses and mobility restrictions that came about due to the pandemic, the platform economy offers great potential for new avenues of income generation, and channels for shifting economic activity from offline modes to online ones. While awareness is the first step toward use, the little awareness that there is has not translated into substantial use.

Digital skills a wanting

For citizens to make meaningful use of digital technology, be it to access earning opportunities, education or other digital services, digital skills are an important part of the puzzle.

“General shots of working professionals i“ (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by ILO in Asia and the Pacific

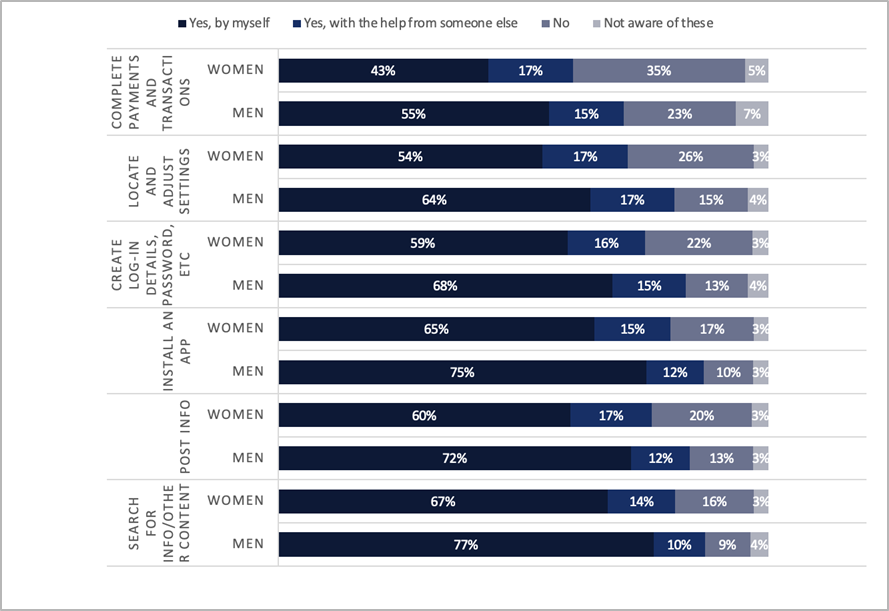

To gauge the level of digital skills, the survey asked respondents about their ability to complete various tasks online. These ranged from basic information searches, to creating and managing online accounts for online services and apps services, to the more complex online payments and transactions. The results show that while overall Indian internet users report higher levels of digital skills than Sri Lankan counterparts, there is a considerable gender gap in these skills levels, with Indian women lagging (Figure 4). For instance, among Indian internet users in the 15+ age group, 68% of males compared to 59% of female internet users are able to create log-in details and set up a password to use an online service or app by themselves. This implies that in order to set up a profile for a digital work platform, many women would either have to rely on someone else to set up their account (and we know from previous research this is often a male family member), or simply would not be able to do it at all. The ability to make use of digital platforms for earning and empowerment is therefore lower among Indian women who are online — and again, we know that women are far less (37% less) likely to be online in the first place in India.

Indian internet users report higher levels of digital skills than Sri Lankan counterparts, but there is gender gap in skills levels, with Indian women lagging.

Figure 4: Digital skills: India (% of 15+ internet users that can complete the following tasks online)

Source: LIRNEasia survey data (2021)

Note: Based on self-reported ratings of ability to complete the relevant task online either independently, with help, or not at all.

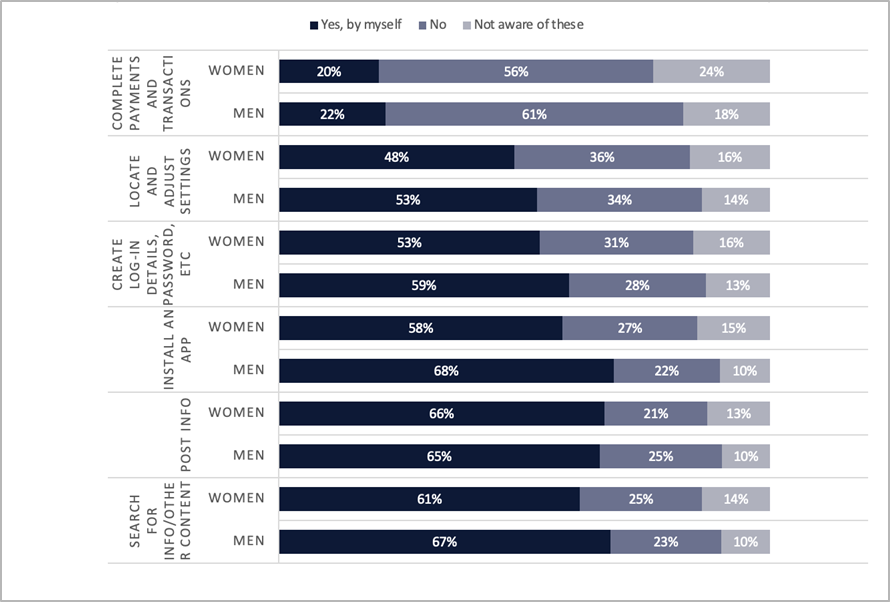

Though Sri Lankan women who are online appear to be almost as skilled as Sri Lankan men online, the survey indicates that there are still significant number of men and women that are unable to set up and manage accounts for services online and engage in transactions (Figure 6). For instance, 31% of women internet users and 28% of men internet users in Sri Lanka did not know how to create log-in details and passwords for services and apps online (while many were just not aware of such tasks in the first place). Over 75% of internet users in Sri Lanka — male and female — were not able to complete payments and transactions online.

The ability to earn and be empowered by digital technology — even among those who are simply online — is constrained by the level of skill and awareness to make use of such opportunities. While the COVID-19 crisis has pushed economically active populations in both countries to learn new digital skills (15% in India and 18% in Sri Lanka as per survey responses), there is still a long way to go.

Significant number of men and women are unable to set up and manage accounts for services online and engage in transactions.

Figure 6: Digital skills: Sri Lanka (% of 15+ internet users that can complete the following tasks online)

Source: LIRNEasia survey data (2021)

Note: Based on self-reported ratings of ability to complete the relevant task online or not at all.

The many facets of the gender digital divide

The findings from the two countries reveal several facets of the gender disparities in both countries, underscoring that the gender digital divide is more than the difference between the haves and have-nots.

“Tamseel Hussain” (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by ILO in Asia and the Pacific

On one hand, in India, where the survey data also shows that women in the 15+ age group are 37% less likely to be online, women are also less likely than men to be aware of digitally-enabled earning opportunities, to use them, and to possess digital skills. On the other hand, in Sri Lanka, these gender gaps have been ironed out somewhat; at least at first glance: women from the same age group are only 7% less likely than men to be online, and are likely to be almost as likely to be aware of and use digitally-enabled opportunities, and possess digital skills. However, the perceptions of the benefits and challenges of working remotely provide a sliver of insight into how that experience varies considerably between men and women, in a way that access, awareness and use statistics do not show. Even once women appear to be ‘on par’ with men in terms of access to or use of technology, how they actually experience technology, and how this relates to their empowerment, can be vastly different.

About the research:

These findings are based on nationally representative face-to-face surveys of the aged 15+ populations of India (excluding Kerala) and Sri Lanka conducted by LIRNEasia. Kerala was excluded due to the COVID-19 situation at the time of survey, rendering fieldwork impossible at the time. The survey samples consisted of 7,000 households in India across 350 villages and wards, and 2,500 households in Sri Lanka across 125 GN Divisions. The sampling methodology has been designed to ensure representation of the target group (population aged 15 and over) at a national level with a confidence level of 95-percent and margins of error of +/-1.7% in India, and +/-2.8% in Sri Lanka. The surveys were conducted between March and October 2021. In addition, the findings were supplemented with work done a project entitled Digital Platforms and Women’s Work in India and Sri Lanka, examining emerging patterns of digital work and women’s engagement with it. Both these projects were funded by the International Development Research Centre (Canada). The LIRNEasia research team consisted of Helani Galpaya, Gayani Hurulle, Tharaka Amarasinghe, Ruwanka De Silva, Oliver Keimweiss and Neema Jayasinghe. The author acknowledges the valuable comments and assistance on this article received from members of the research team, as well as Mukta Naik, Sabina Dewan, and Prerna Seth of CPR (India).