Decarbonization is among the greatest imperatives of our time—key to arresting the planetary warming catalyzed by human activity. The climate shocks of 2025 have only underscored the need to reduce emissions, as treacherous floods ripped through the Indian Himalayas, deadly wildfires scorched Los Angeles and the Canadian Plains, and heat waves parched an unprepared Europe.

But despite the reams of research dedicated to climate science, mitigation, and adaptation, we still know relatively little about how the global shift to low-carbon technologies will reshape human economies and labour markets.

Most conversation around decarbonization and jobs focuses on a narrow set of questions—how many jobs will be lost in fossil fuel sectors and how many will be created in renewable energy sectors. Occasionally, debates extend to questions of labour in the mining of critical minerals needed for low-carbon technologies.

Social scientists argue that decarbonization is a “socio-technical transition,” a deep and far-reaching reorganization of technology, policy, infrastructure, society, and economy. Past energy transitions—for example, from wind, water and animal power to fossil fuels—unleashed a profound restructuring of labour markets. In his work on “fossil capital,” Andreas Malm argues that the adoption of fossil fuels in the 19th century enabled industrialists to concentrate production and exert more control over workers.

If indeed we stand on the precipice of an energy transition as profound as the one that established “fossil capital” as the grease of the global economic order, then the impacts on workers and communities will extend far beyond the energy sector itself. The “second order” effects of decarbonization—its impacts in all the other parts of the economy—are likely to influence many more people’s access to jobs.

The problem is, we still know relatively little about these broader impacts of decarbonization on labour markets.

JustJobs Network is seeking to address this knowledge gap through its leadership of the FutureWORKS Collective, an initiative funded by the International Development Research Centre involving collaboration among research institutes across the developing world.

Our first project under the banner of decarbonization and jobs examines how India’s transition from internal combustion to electric vehicles—a key pillar of its decarbonization strategy—will affect regional economies and labour markets. The auto sector plays a big role in India’s labour market, employing 4.2 million workers directly and 26.5 million indirectly.

Our research asks: What is the emerging geography of jobs in electric vehicle manufacturing, and how does it compare to the geography of jobs in traditional ICE manufacturing? What does this mean for India’s bigger challenge of addressing regional inequality?

To tackle this question, we used quantitative statistics from the Annual Survey of Industries, Periodic Labour Force Survey, and All India Council on Technical Education; qualitative interviews with key informants holding relevant experience or expertise in the auto sector; and policy documents from 13 major states that have introduced electric vehicle industrial policies aimed at attracting, retaining, and growing firms specialized in EV production.

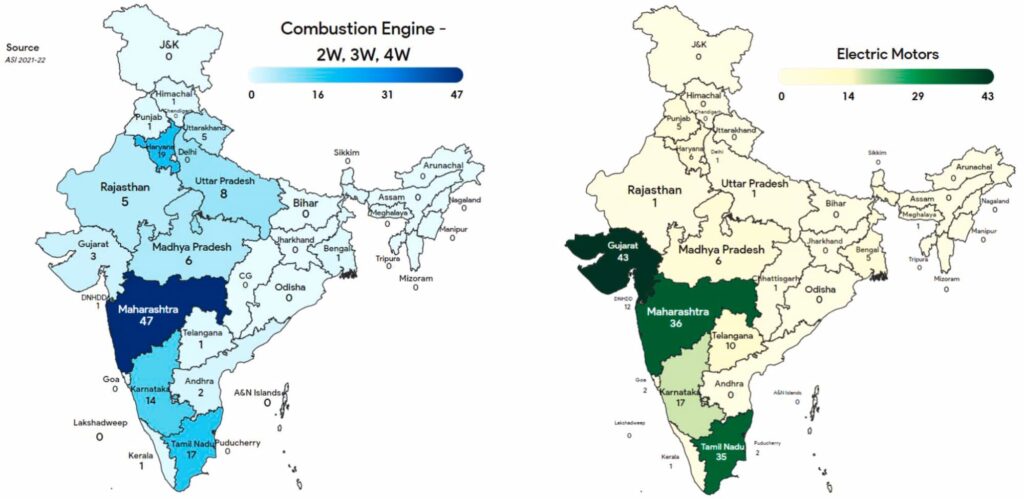

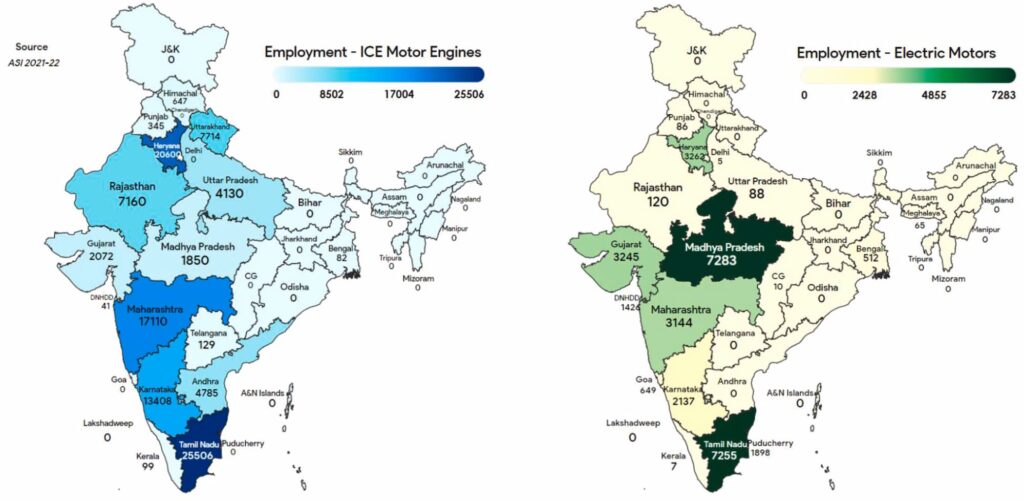

We find that the low-carbon transition in the auto sector is likely to reinforce rather than redress regional disparities in India—with the south and west benefiting most from the transition. Lower-income states in the country’s east are not establishing any foothold in the EV supply chain. And among those states with preexisting auto manufacturing clusters, the south is seeing faster development of the EV sector, given its higher-skilled workforce, vocational training infrastructure, and private sector culture of technology and innovation.

ICE and electric motor firms (2021-22)

ICE and electric motor employment (2021-22)

Shift in skill requirements due to EV transition

|

Skill Level (NSQF)5

|

Share of Obsolete Job Roles in ICE ecosystem (%)

|

Share of New Job Roles in EV ecosystem (%)

|

|

2

|

10.6

|

2.1

|

|

3–3.5

|

7.6

|

6.5

|

|

4–4.5

|

48.5

|

37.6

|

|

5–5.5

|

31.9

|

38.7

|

|

6

|

1.5

|

15.1

|

Source: iFOREST, 2024

Why? Jobs in EV production require higher skills than jobs in ICE production, as research by iFOREST has also shown. ICE manufacturing is dominated by mechanical engineering and automotive assembly, but EV manufacturing involves roles related to battery management systems, electric motor production, and software development for vehicle integration. Workers with these skills are easier to find near the country’s IT hubs.

What’s more, southern states like Tamil Nadu are building on their advantages by adopting a wide range of policies for upskilling workers, subsidizing job creation, promoting R&D, and introducing new EV vocational courses.

Electric motor production, growth in share of total employment and firms (2017–2022)

|

State

|

Growth in Employment

Share (2017-22) (%-point) |

Employment Share (2022)

(%) |

Growth in Firm Share (2017-22) |

Firm Share (2022)

(%) |

|

Dadra & N Haveli

& Daman & Diu |

4.56

|

4.56

|

6.14

|

6.52

|

|

Goa

|

0.46

|

2.08

|

0.32

|

1.09

|

|

Gujarat

|

0.23

|

10.4

|

2.76

|

23.37

|

|

Haryana

|

1.57

|

10.46

|

1.35

|

3.26

|

|

Karnataka

|

−0.26

|

6.85

|

−0.68

|

9.24

|

|

Madhya Pradesh

|

−9.98

|

23.35

|

0.97

|

3.26

|

|

Maharashtra

|

−14.22

|

10.08

|

−11.73

|

19.57

|

|

Puducherry

|

6.08

|

6.08

|

1.09

|

1.09

|

|

Punjab

|

−0.43

|

0.28

|

−7.97

|

2.72

|

|

Tamil Nadu

|

11.78

|

23.26

|

6.43

|

19.02

|

|

Telangana

|

0.00

|

0

|

5.43

|

5.43

|

|

West Bengal

|

0.04

|

1.64

|

−1.10

|

2.72

|

Source: Annual Survey of Industries. All included states hosted at least 2% of the total employment or total firms in the sector in either year. Bolded states hosted at least 10% of the total employment or total firms in the sector in either year.

This means that a key component of India’s decarbonization strategy could worsen the gap between its richest and poorest regions. Prior research also finds that the coal-to-renewables transition will favour wealthier states. India already has some of the worst regional inequality in the world.

None of this implies India should stop trying to decarbonize. But it does call for greater attention to how decarbonization will impact the local and regional economies—and thus work opportunities—in places where poverty and poor-quality jobs are most prevalent. India’s EV transition is still nascent, meaning future policies and programs still have a chance to seed growth of EV clusters in lower-income states.

Read more about this research in a recently published journal article, and look out for a JJN policy brief later this year on the topic of India’s electric vehicle transition.